Background & Production

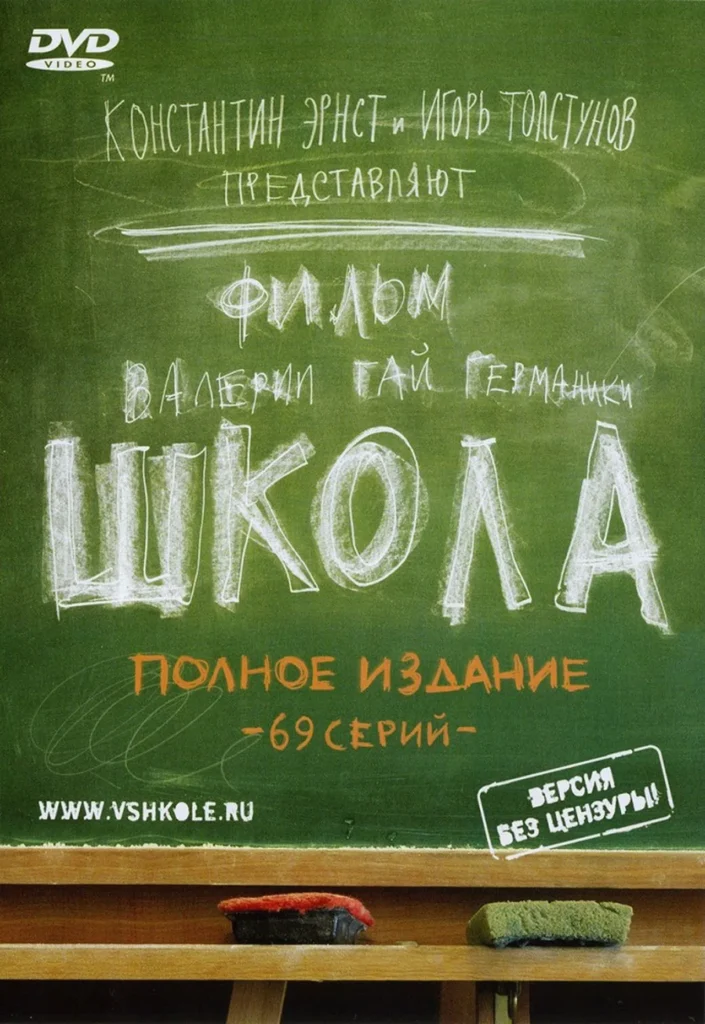

Valeriya Gai Germanika’s School was a bold experiment for Russian TV. Backed by Channel One and Krasny Kvadrat, it was conceived as a raw, author-driven drama about life in a Moscow 9th-grade (“9A”) classroom. Director Germanika (already known for edgy youth films like Everyone Dies But Me and Girls) aimed to depict teens “as they really are,” with all their conflicts and confusions. The producers even launched an interactive social network (vshkole.ru) to let real students share their school experiences – Germanika reportedly incorporated some of those stories into later episodes. Channel One committed to a single season of 69 episodes, airing twice daily, targeting both teenage and adult audiences. Executive Igor Tolstunov noted there would be no second season, and he dismissed rumors of on-set strife or departure: filming finished at the real school location without delays. (Indeed, social backers and even teachers at the school reportedly cooperated rather than staged any shutdown.) Some early scenes were censored on TV – for example, certain graphic scenes were cut for broadcast and held for the later DVD release – underscoring just how provocative the material was. In short, School was a high-profile “auteur” project on a state channel, an unusual gamble meant to provoke conversation. (Media scholars later noted that, unlike milder teen shows of the era, School quickly became “the epicenter of protracted media discussions” in Russia

Plot & Characters

The series opens after beloved teacher Anatoly Nosov (the class’s “strong hand”) falls ill and can no longer lead 9“A.” Discipline crumbles. Nosov’s granddaughter Anya “Marla” Nosova (Valentina Lukashchuk) – a moody emo teenager raised by her grandparents – is one of the most rebellious students. A new boy, Ilya Epifanov (Aleksei Litvinenko), suddenly transfers in from a prestigious boarding school. In the very first episode, Ilya immediately shakes things up: he boldly calls himself both a “goof” and a “personality,” throws a punch in a hallway squabble, and even disrupts a physics class (the kids mock the lesson on “oscillations” with snide laughter). That physics lesson scene sets the tone: instead of a neat sitcom setup, the camera lingers on restless teens. (Later at the teacher’s birthday party, “truly horrible things happen, including a Russian folk dance ‘Valenki’,” hinting at the chaos underlying the seemingly normal school setting.)

Other classmates orbit these central figures: Olya Budilova (Anna Shepeleva) is the class “beauty,” an aspiring ballerina; Irina Shishkova (Natalya Tereshkova) is a passionate folk dancer; and student Vadim Isaev (Aleksei Maslodudov) leads a skinhead clique. Russian language teacher Valentina Murzenko (Elena Papanova) stands in for the absent Nosov and struggles to maintain order. Over the season we see classic high-school themes played out with unvarnished intensity: bullying and clashes (Marla’s emo angst, Olya’s romantic tensions), clashes with authority (Nosov’s old discipline versus the unruly teens), and dark secrets. For example, Marla quickly develops an unhealthy fixation on Ilya, a storyline hinted at through love letters and personal journals (explored more in tie-in novels). By the finale, the mix of peer pressure, harsh pranks and misunderstandings has escalated to serious crises (one reviewer bluntly observed that the series ultimately implies “school is hell, and the only solution is suicide”). Throughout, the ensemble acting (mostly by real teens) and overlapping story threads – no single “plot of the week” – give School a slice-of-life feel. TMDB’s summary captures this: “the class’s myth of an exemplary cohort collapses” after Nosov’s illness, and the new pupil Ilya “proves situations in which students manifest unexpected sides, turning upside down the usual idea of them as classmates and teachers”

Cinematography & Style

Germanika’s direction favored a gritty, almost documentary style. The camera often weaves through crowded hallways and hovers on handheld shots of teens talking quietly in corner, as if observing actual students rather than stage actors. For example, in this official still from the series (below), a group of indifferent 9th-graders loiters in a corridor – their posture and expressions totally unguarded. The scene looks like a chance snapshot of high school life, not a polished studio set

A candid hallway shot from School, showing students hanging out at lockers. The handheld camera style and natural lighting make it feel hyper-real, underscoring the series’ raw, quasi-documentary aesthetic

This visual approach was deliberate. Film critic Marina Razbezhkina (who co-directed School) later explained that her cinematography choices were meant to “only enhance the authenticity of the spectacle”. A Film.ru reviewer noted the “mad handheld camera” whipping through scenes, capturing every twitch and glance. (He even joked that in the premiere, the camera’s “oscillating movements” matched the physics lesson on oscillations – the metaphor was intentional.) The acting direction likewise favors non-actors and improvisation: many characters speak in authentic teen slang and behave unpredictably, rather than delivering neat scripted lines. The net effect is akin to cinéma vérité. Some critics admired this: as Rock critic Artemiy Troitsky put it, School is “an island of truth” in the usual sea of artifice. Others, however, found it uneven. Koresky of Afisha noted that the loose, multi-author script could “lack energy and inventiveness” at times. In particular, the series consciously forgoes a classic TV formula: there is no single hero or self-contained plot per episode. Instead it unfolds more like a very tightly integrated telenovela, or a day-in-the-life, hooking the viewer through its atmosphere rather than a clear-cut storyline. This bold choice keeps viewers on edge (it’s easy to get hooked and not want to switch away), but it can feel disorienting if you’re expecting neatly resolved arcs

Reception & Ratings

Reactions were passionate. Critics generally praised the authenticity and performances. Afisha critic Roman Volobuev singled out the young cast and tight close-ups, and emphasized how remarkable it was for such an “auteur-driven project” to be shown on national TV. Blogger-turned-critic Dmitry “Goblin” Puchkov lauded School as “very well made” and sharply different from anything else on Russian TV. Artemiy Troitsky declared himself a fan: he called School “the best thing that has ever been created on state television” in post-Soviet times and praised it as refreshingly truthful. Interview magazine even described the show’s inverted logic: “friendship can be seen only in a quarrel,” highlighting the edgy approach. Awards also followed: in 2010 School won the TV-Press Club’s “Television Event of the Season” for “fearless experimentation”, and its producers took home a TEFI award. By some measures it was a hit – Tolstunov noted “very good” ratings for School, and Channel One was pleased with its performance. Notably, a national survey found about one-third of all Russians had tuned in to watch School, a staggering reach for any drama.

However, the show was too intense for some tastes. On aggregate sites, School holds a moderate score: IMDb shows roughly 6.4/10 (from about 1,000 votes). (TMDB lists no official user score without login, and Rotten Tomatoes does not list it.) Many Russian viewers found it either riveting or upsetting. In the Internet era, fans posted mixed reactions: some praised the raw realism as overdue, while others complained that the series was relentlessly bleak. Social media buzzed with debates about which characters were over-the-top or spot-on. Regardless, the consensus was that this was no run-of-the-mill TV drama.

Audience Response & Controversy

If critics were divided, officials were mostly furious – and their outcry only fueled the show’s fame. School prompted an unprecedented nationwide debate about the state of education and youth culture. After just a few episodes, Moscow’s education commissioner Olga Larionova publicly demanded it be pulled from the air. Regional officials joined in: cultural ministers in Penza, deputies in Ulyanovsk, Volgograd, Ryazan, and even Krasnodar’s ethics council all condemned the series as scandalous. Duma deputies Tamara Pletnyova and Irina Yarovaya called it out, and one MP (Vladislav Yurchik) lambasted School on the Duma floor as a “planned diversion against our children and youth”. Even as conservative voices criticized it for “half-truths” (Education Minister Fursenko insisted “not all our schools are like that”), there were defenders: President Putin visited a university in Chuvashia and observed that School “shows the point of view of the authors” and tackles problems that are “relevant” today. Church leaders weighed in too – Patriarch Kirill said the grotesque depiction did shine a light on what is happening with kids (and reinforced the need for moral education), whereas other clergy voiced concern that the series lacked moral guidance.

The uproar was not just official. Educators were split: veteran teacher Efim Rachevsky (a member of the Public Chamber) denounced School as “absolute blackness about teachers,” saying it left him personally demoralized about the profession. Many parents and pundits echoed that sentiment, writing open letters and demanding censorship. In response, Tolstunov urged skeptics to withhold judgment until they’d seen the whole story: as he pointed out, by the finale “all the kids are very good – doing very good deeds”, and the intention was to portray multi-dimensional young people, not one-sided villains. He even likened School to the classic Russian school drama “We’ll Live Till Monday”, saying his goal was “to understand this generation… and help them understand the life they are entering”.

Despite the furor, the series left a cultural mark. It sparked countless articles and talk-show segments about youth, even led to four tie-in novels that explore unseen events from the show’s universe. In the context of Russian media – where teen dramas were typically light or propagandistic – School stands out as a hard-edged outlier. Its honest (if sometimes brutal) portrayal of adolescent life forced society to confront issues usually glossed over on TV. Even critics who found the series uneven agreed it was important. As Gulchita (a media scholar) observed, School became “an island of truth” amidst mainstream TV’s usual spin

Verdict – 8/10

School is not an easy watch, but it’s a rare one. Its strengths lie in its fearless authenticity: the unpolished cinematography, the naturalistic performances by real teens, and the willingness to tackle taboo topics (peer violence, family dysfunction, etc.) give it undeniable power. It captures a snapshot of post-2000s Russian youth in a way few productions have. On the other hand, its very rawness can feel sensationalist or incoherent – the plot threads sometimes meander, and without strong moral frames, viewers must do a lot of interpretation. It’s arguably uneven and polarizing, but that’s also part of its point: a perfect TV show might not spark the kind of debate this one did.

In the end, School earns points for daring realism and cultural impact. It remains a significant work in Russian television history, especially because it got such a prominent platform. The series may frustrate you with its lack of neat resolutions, but it will stay in your mind longer than many slicker dramas. For its raw vision and courage to show youth “as they are,” we give School 8 out of 10